Stopping Piracy Like a Boss

Piracy is something I really don’t care about that much. Unless it affects me. Then I get slightly mad. I don’t steal content myself - the vast majority of music I own is ripped from my own CDs, or purchased online. I’m not a big TV person, or a big gamer, or a big movie-watcher for that matter - but when I do partake, I purchase.

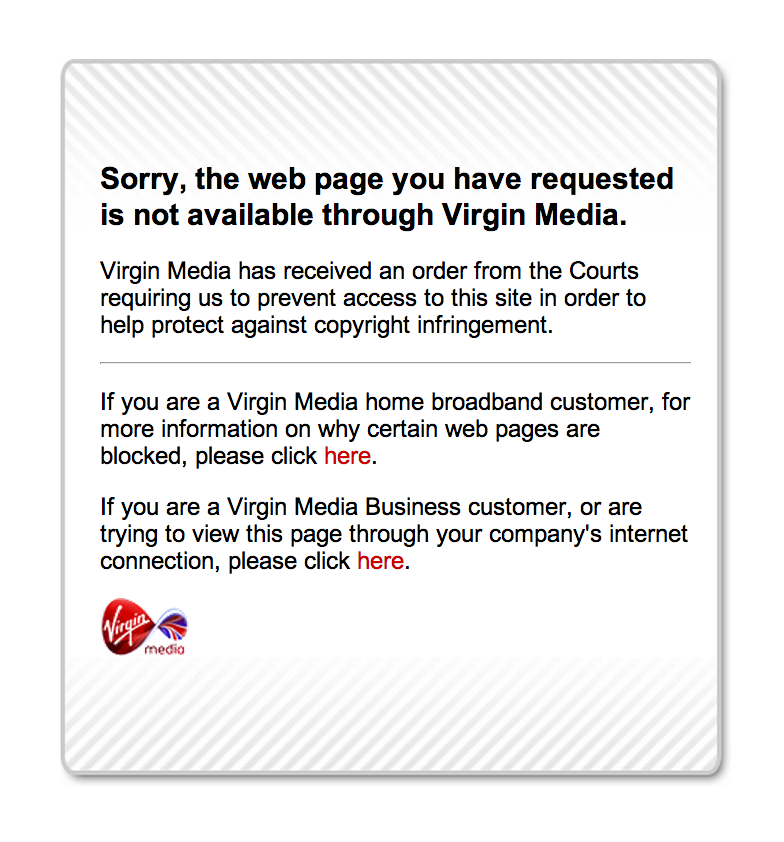

Things that do annoy me, however, include inefficiency, wastage and breaches of my privacy… Virgin Media, my ISP, have just commenced another round of site-blocking -ordered by the Courts - to prevent their customers from accessing certain sites that provide streams of TV shows for free. The likes of vodly.to and primewire.ag now join The Pirate Bay in an exclusive but rapidly-expanding club of blocked sites in the UK.

The actual technical details behind the blocking seem to be widely debated so I thought I’d put together a simple little investigation into how Virgin have set it up. If you’re new to this sort of thing, it’s also a good primer on DNS, HTTP and a little of how the Internet and the WWW work in general.

Vodly.to & CloudFlare

I’ll use vodly.to as an example because it has a more interesting configuration than say The Pirate Bay. Vodly uses CloudFlare - a HTTP reverse proxy service that is designed to shield the site from DDoS attacks and mask its real IP address from the outside world.

The first thing to realise about Virgin Media’s blocking is that it is not DNS-based. They do not poison their DNS cache entires or MITM (Man In The Middle) DNS requests at all. The blocking is actually more sophisticated but, some would argue, more invasive…

Let’s perform a DNS lookup for vodly.to:

$ dig vodly.to

>>> snip >>>

;; ANSWER SECTION:

vodly.to. 300 IN A 190.93.241.35

vodly.to. 300 IN A 190.93.242.35

vodly.to. 300 IN A 190.93.243.35

vodly.to. 300 IN A 141.101.112.36

vodly.to. 300 IN A 190.93.240.35

>>> snip >>>So… vodly.to has a number of IP addresses, all of which happen to be CloudFlare proxies. Lovely.

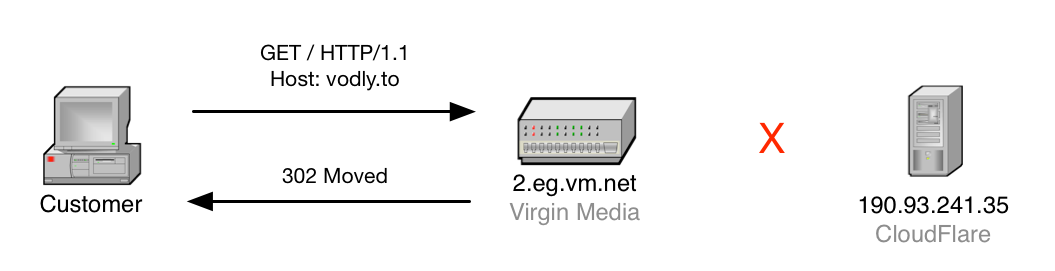

Let’s send a HTTP request using netcat to one of them and see what sort of response we get back:

$ echo "GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: vodly.to\r\n\r\n" | \

nc 190.93.241.35 80And the response?

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Location: http://assets.virginmedia.com/site-blocked.html

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

<HTML><HEAD><meta http-equiv="content-type" content="text/html;charset=utf-8">

<TITLE>302 Moved</TITLE></HEAD><BODY>

<H1>302 Moved</H1>

The document has moved

<A HREF="http://assets.virginmedia.com/site-blocked.html">

here</A>

</BODY></HTML>So, what happened here? It looks like the CloudFlare server returned a redirect page to Virgin Media’s “Site Blocked” page.

Actually, the request we sent never reached CloudFlare’s server and was intercepted by a middle-man on the way that fed us the redirection page in the response above.

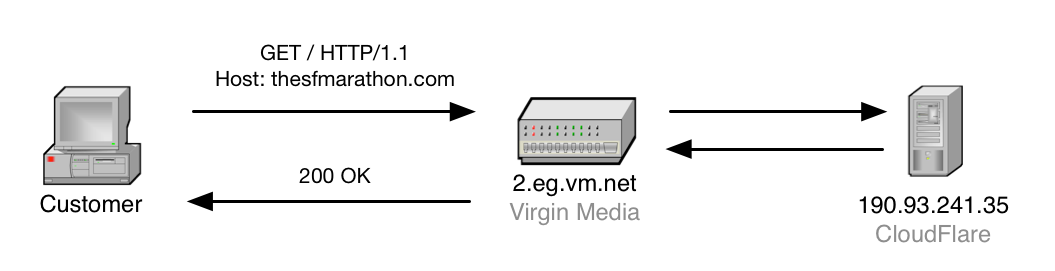

This is interesting, because it means that all requests sent to CloudFlare proxies from Virgin Media customers are being inspected. How about if we make a request to the same IP address but request a different CloudFlare-protected site in the Host: field? Let’s make a request for The San Francisco Marathon’s website which, I discovered while browsing CloudFlare’s website, is a CloudFlare-protected site…

$ echo "GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: thesfmarathon.com\r\n\r\n"\ |

nc 190.93.241.35 80The response? Well I won’t paste the response text here, but it’s a loader page for the San Francisco Marathon website. It works - no blocking.

The conclusion we can draw from this is that some Virgin Media core routers inspect every request on the way to CloudFlare’s servers, determine if the Host: HTTP header value is one of the blocked sites that is known by them to use CloudFlare and if so, respond with a 302 Moved status to redirect the user to their block explanation page.

Questions

This raises some interesting questions. What would Virgin do for CloudFlare-protected sites that use SSL (and I mean what CloudFlare call “Full” SSL, where the connections on both sides of the CloudFlare proxy - to the user and to the site server are SSL’d). This would of course hide the Host: HTTP header from Virgin’s routers and would make it impossible to tell which requests were for blocked sites. This would pose an interesting challenge for their network engineers I’m sure - in reality they’d probably end up having to fall back on DNS poisoning.

Another question is, where does the tampering happen? I need some help figuring this out, though I have some suspicions derived from looking at traceroute results for various sites from a Virgin Media connection. It could just be the way Virgin have their peering set up, but it looks like all CloudFlare IP addresses are routed through some “usual suspects” that always crop up in the traceroute trails.

Thoughts

This all means that Virgin Media have the infrastructure in place to inspect packets, down to the application layer, as they pass through their network. On a large scale. CloudFlare is huge. It specifically attracts high-traffic sites, so Virgin must be able to do this en-masse without too much performance impact.

I also note that the blocking is rather shoddily implemented. For example, while requests with Host: vodly.to are intercepted, requests with Host: www.vodly.to are not. All of Vodly’s assets are hosted from the non-www domain, so the images and stylesheets won’t load, but the markup loads just fine for www.vodly.to. Virgin are really just banking on Vodly’s lack of domain-agility.

Aside: A friend of mine and I were just investigating the mechanism in more detail - it turns out that at least for Virgin Media, they intercept all requests to CloudFlare IPs used by Vodly that have the Host: field set to anything matching vodly.to, yet _not_ vodly.to. The wrong way around. I have set up http://vodly.to.damow.net to test this. Give it a go!

Impacts

Piracy will laugh in the face of this. I consider this kind of thing the online-equivalent of a war on drugs. In most cases, they just stoke the fire - turning the landscape over a little and forcing innovation - opening up new opportunities for new sites. If content producers really want to stop piracy, they need to make their content highly affordable, highly available and totally ad-free. End of.

There are any number of ways to get around this kind of blocking, already - within days, proxy sites are cropping up, replacement sites are gaining popularity and clearly, holes are being discovered in the very mechanisms used to block them in the first place.

It’s a game of whack-a-mole with near-infinite mole-holes and where every hammer blow needs to be authorised by a court.